5 Hunters Who Shaped Modern Conservation

Keenan Crow 12.26.19

It is unfathomable to too many that hunting and conservation are inextricably linked. In fact, hunters, and to be sure it must be said *responsible* hunters, are primary beneficiaries of conservation, after the animals themselves. It is natural for them to take a responsible interest in the wild.

To that end, a brief look at a few hunters helped shaped the modern conservation is not out of order. Because pop culture is certainly familiar with the likes of PETA and Steve Irwin and even Jane Goodall (who supported sustenance hunting for herself when she was in the field), the subject of hunting – whether it be “trophy hunting” or even culling hunts – have become a sort of political hot button subject. The idea that hunting for food AND sport can be responsibly used to help population controls has become abhorrent in main stream, even though it was hunters who first promoted and continue to this day to utilize responsibility in conserving wildlife and natural habitats for future generations’ enjoyment.

John James Audobon (1785-1851)

While it is difficult to pinpoint any one individual who could be the “first” conservationist hunter, the Audobon name is strongly linked to the practice. Following in the tradition of Daniel Boone and perhaps setting a standard for later Charles Darwin, the naturalist and painter that was to become Audobon was born Jean Rabin on April 26, 1785 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), the result of an extramarital arrangement between a French naval captain turned sugarcane plantation owner and one of his servants. Within a few years, Jean was brought back to France and formally adopted into his father’s family, exchanging Rabin for Audobon and after a short dalliance in the French Navy’s officer program was permitted to pursue his interest in nature before he was sent to look after his father’s business ventures in the US where he anglicized his name to John.

Over the course of the next two decades John mixed import/export goods to the frontier along with becoming acquainted with American wildlife and Native American customs of several tribes for which he developed a lasting respect and admiration. It was during this period that he both gathered knowledge as well as furthered his artistic and taxidermy skills that he ultimately compiled into a collection of pictorial and text studies. There were actually multiple incarnations of these studies that were in turn either discarded or otherwise destroyed before forming into the first portfolio The Birds of America. His collection of color plates became popular in the US, UK, France and beyond.

Many are now familiar with the Audobon name and its associations with ornithology and bird sanctuaries, John brought awareness of the many fascinating bird species by hunting them: this was the 19th century equivalent of bringing them out of their habitats for viewing on nature channels today, without the possibility of release. Nevertheless, without his efforts, much of what was still the untapped West would have been left in mystery leaving more than a few species to slip into extinction without earlier references to them.

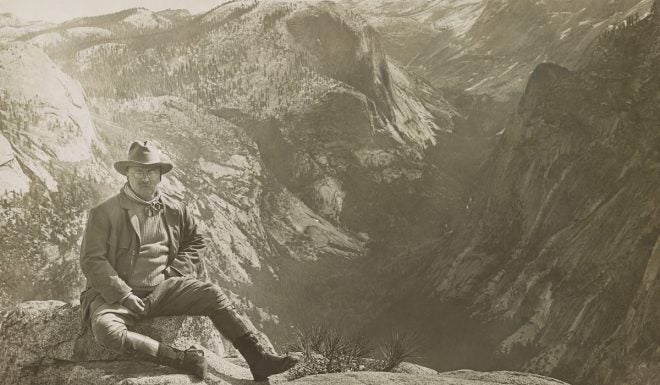

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919)

Perhaps the most obvious of conservator hunters would be none less than “Teddy” Roosevelt. This is no doubt largely due to his progressive (contemporary) reforms that became codified into federal laws during his presidency. Roosevelt had developed an early fascination with nature as a child but more famously developed a strong respect and appreciation for nature while working as a cowboy after the same day deaths of his first wife Alice and his mother in 1880. Actually, he had not begun his dalliances in “cowboy life” until 1884 when he took a hiatus from New York politics. He was himself a product of a growing movement that exalted the natural world that had been taking form during the 19th century, nudged along by writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

As an acolyte of the belief that man had a custodial responsibility to the natural world, Roosevelt was motivated by the reckless waste of industry and agriculture that was stripping away Americans’ heritage. The conservativism that Theodore ultimately adopted often fell short of what other preservationists – contemporary as well as succeeding – wanted but he recognized the strength of market forces that included drilling, mining and logging. Rather than prohibit such practices, he sought to redirect them away from preservations and protected areas.

As president he developed a reputation for monopoly breaking, but his policies still recognized that the environment would be looked to for industry and economic growth: something as a national leader he had to remain conscientious of. There was no escaping it from his point of view, and this was where he fell short in the opinion of other preservationists. Regardless, he took the momentous step of limiting the excesses that property owners could do with their own property when it came to irrevocable harm to the natural world. To that point, the federal government had taken a hands off sort of approach which he essentially upended: as president Roosevelt established the United State Forest Service, created five national parks, 150 national forests, 51 bird reserves, four game reserves and placed under public protection a total of approximately 230,000,000 acres.

He also helped cofound the Boone & Crockett Club which is still at the forefront of sportsmen conservationism. Perhaps most endearing is the club’s furthering the sentiment that game animals are to be treated with respect and dignity: most famously related in the story of Roosevelt’s refusal to shoot a trapped bear.

William Temple Hornaday (1854-1937)

Hornaday (not Hornady) began his professional life as a taxidermist for the Natural Science Establishment in Rochester NY where he endeavored to expand the institution’s specimens, first by travelling to southeast Asia (relayed in Two Years in the Jungle 1885). He more became famously noted for his work with what would become the Bronx Zoo: first attempting to document the American Buffalo before its considered inevitable extinction and finally in the preservation of the species. Similar to Audobon’s cataloging, the collection of samples required their being hunted. However, Hornaday also worked to collect live samples of American bison ultimately delivering over three dozen of the animals to reside in the Bronx Zoo’s open range.

Together with his contemporary Theodore Roosevelt, Hornaday is credited with the survival of the buffalo through the American Bison Society. Through his endeavors with the zoo he established a strong sentiment for the preservation of wildlife. To be sure, not all of his efforts were what would be deemed politically correct, and even his contemporaries who were avid hunters may have raised an eyebrow to his objection to the threats of modern conveniences (the automobile and modern firearms) posed to nature. Rather than being antagonistic, however, his views were a legitimate warning. Our Vanishing Wildlife, published in 1913, could easily be read as a call for caution and restraint in a growing penchant for excess in an age of the great leaps the Industrial Revolution allowed to more and more people: hunters were no longer hunting for sustenance or made up into a minority of rich or aristocratic elites, but as more people found opportunity for leisure and recreation, their ignorance and excess posed a very real threat that Hornaday saw first hand in the near extinction of the Buffalo.

His writings on conservation and ecology nevertheless became, and even remain, a strong influence on the teachings within the Boy Scouts of America, with his name attached to the coveted Wildlife Protection medal after his death. While his earlier career as a hunter was something he shied away from in later life, it was these experiences that encouraged later hunters to have respect for the natural world.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

Born in Iowa Leopold, like many conservationists before and since, was an avid outdoorsman from an early age. These talents and skills ultimately found him contracted by local ranchers to kill bears wolves and mountain lions. On one occasion he experienced a sort of awakening after taking down a wolf that led him upon a path reconsidering natural predators and their important role in the environment. This new “ecocentric” outlook deviated from the previous school of thought that promoted humanity as a dominant authority in nature in favor of a new policy in which humanity must play a supporting role, especially in light of mechanical advancements: specifically the automobile and its primary (access to the wilderness), secondary (collisions with animals of the wilderness) and even tertiary (pollution in the wilderness) effects upon the natural world.

Leopold’s conservation philosophies were most famously set forth in his work A Sand County Almanac (published the year after his death 1949). Among his assertions was that mankind had an ethical responsibility to maintaining the wilderness (which included predators) that went beyond the utilitarian approach to conservation that was promoted by Teddy Roosevelt.

Instead he promoted developing a scientific management of habitats by both private and public landholders in lieu of relying on game refuges and laws to protect desired game animals. His earlier book Game Management (1933) defined the goal of his developing process of conservation to provide sustainable annual crops of wild game for recreational use, but he also promoted it to facilitate a return to the wilderness a desperately needed environmental diversity.

In 1935 he helped found the Wilderness Society which was founded with the intent to expand and maintain wilderness areas. It was a manifestation of what he deemed a reasoned humbleness on the part of mankind and society toward humanity’s place in nature. In some ways he can be compared to an earlier time where he and Thoreau could share quiet walks of contemplation; he certainly receives recognition of a more modern perspective of spirituality in nature from a mutual respect for all its vast assortment of life: even those who were once deemed a menace.

William Holden (1918-1981)

Thanks to his starring rolls in Stalag 17, The Bridge on the River Kwai and of course The Wild Bunch (among others) Holden’s (born William Franklin Beedle Jr.) acting career is well known, but his work in conservation is somewhat less so. In 1959 Holden founded the Mount Kenya Safari Club in Nanyuki, Kenya which became a popular destination for the international jet set of the early 1960s. Initially a game hunter himself, Holden witnessed firsthand and became concerned with the decreasing animal populations from loss of habitat and poaching.

With help from partners in the Club grew into the Mount Kenya Game Ranch and ultimately into the William Holden Wildlife Foundation. Within the Game Ranch is the Mount Kenya Conservancy that partners with the Kenya Wildlife Service running a wildlife orphanage and the Bongo Rehabilitation Program. The aim of the orphanage is to restore to health injured and or neglected animals so that they may be released back into the wild whenever possible. The primary focus of the conservancy is protecting the endangered East African mountain bongo.

In 1972 Holden began a relationship with actress Stephanie Powers, inspiring her interest in wildlife conservation. It was Powers who, after Holden’s sudden death in 1981, began the William Holden Wildlife Foundation (WHWF) within the Game Ranch. In the years since, the WHWF has built libraries, water purification facilities, natural history displays and partnered with local and international schools to promote a stronger understanding of the important role of natural wildlife in to the environment and the world at large.

The popularly assumed irony of hunters becoming the primary defenders of wildlife is not lost on outdoorsmen themselves. We are the first to notice the decline in the environment after the animals themselves. While the aim of conservation may spread over the goals of husbandry or for recreational to subsistence hunting, the far reaching goal is the same: to maintain a stable and thriving natural world for future generations to enjoy. This requires a calculated and responsible custodianship that hunters are uniquely suited to appreciate and implement.