A River Might Run Through It

Bob McNally 07.07.15

This may not be on an emotional par with global warming or long-line over fishing for marine pelagics; but diverting huge quantities of freshwater to satisfy development in boom areas of coastal America can, and will, impact the future of fishing and perhaps the way Americans live.

A good example of this is the St. Johns River in Northeast Florida, upon the shores of which I’ve lived for over 30 years. The St. Johns winds north, slow and free-flowing for over 300 miles from central Florida to the Atlantic Ocean near the town of Mayport, east of Jacksonville.

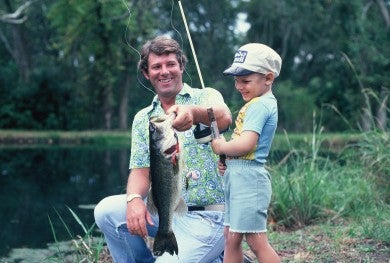

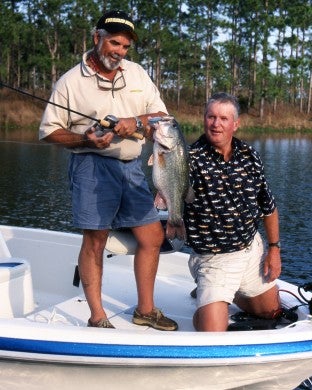

For most of its length, the river is a freshwater haven for bass, catfish, crappies and other species. But the river is unique in many ways, as it harbors species from anadromous striped bass and American shad (the southern natural limits of both those marine fish) to tropical snook (the northern natural limit for that great gamefish). Tarpon, redfish, flounder, black drum, mullet, menhaden, American eels, shrimp, blue crabs, oysters, barnacles, and a multitude of other important brackish and saltwater species also inhabit much of the lower 50+ miles of river.

The St. Johns, like many large coastal rivers, is a curious mix of freshwater (upper river), brackish water (middle river) and saltwater (lower river), that has enriched the Atlantic Coast marine ecosystem and allowed countless aquatic species and plants to thrive for uncounted thousands of years.

During years of drought the lower river is very salty. In years of abundant rainfall the river’s “saltwater” area moves downstream. There is no definitive line of where freshwater ends, brackish begins, and saltwater reigns. And that’s how it’s supposed to be. It’s an interesting natural system that cleanses the river, keeps it and its aquatic species healthy, vibrant, and capable of surviving almost everything that even man can do to turn the tide of nature.

Until, perhaps, now.

The St. Johns River Water Management District is a politically-appointed board in charge of the river and its resources. It has a controversial plan for re-directing fresh, spring water from the headwaters of the St. Johns to Central Florida and Orlando. This is designed to satisfy the thirst of millions of new-growth people, with more moving in daily. Population in the counties served by the St. Johns River Water Management District was 3.5 million in 1995. It is expected to reach 5.9 million in 2025. They all need water, and there are not many conservation measures in place.

So the simple way of handling huge population growth needs is to get more of what’s wanted–in this case clean, fresh water.

Although charged with preserving the welfare of the St. Johns and its creatures, the river management board is in favor of daily siphoning over 260 million gallons of spring freshwater away from the river and on to Orlando. That’s 260 million gallons, every day, every year–and that’s just to start.

Since there is no end in sight to the human boom and growth of Central Florida, it’s safe to assume such a diversion of water from the St. Johns is only a beginning to a potentially tragic end. It’s the kind of oversize water works project that has been so disastrous to Florida’s Kissimmee River, Lake Okeechobee, and the Florida Everglades.

This alone is reason enough for concern. But the St. Johns has shown grave signs of human misconduct in recent years, with fish die offs and enormous algae blooms (due to fertilizer run-offs, septic tank issues from riverside developments, plus municipal sewage problems). With significantly less spring-fed, clean water flowing into the upper St. Johns River, it’s a good bet that fish, fishing, and the marine ecosystem in the lower river will be dramatically impacted.

Jim Orth, executive director of the St. Johns Riverkeeper (a privately-funded river watchdog organization), says better alternatives for water conservation should be established before such a drastic step in siphoning water from the upper St. Johns is undertaken. He says about half of all potable water in the river water district is used for irrigation, an incredible revelation considering the water crisis facing the St. Johns.

Quinton White, a Jacksonville University biologist who has studied the river since the 1970s, warns about increasing salinity in the river caused by a withdrawal of freshwater. He also says water diversion from the upper river to Orlando could produce more sediment deposits in the lower river.

Virtually no studies have been done to learn what a huge drop in clean, freshwater will have to the lower river ecosystem, which is as diverse and important to anglers as anything on the Eastern Seaboard.

Can such a huge volume drop of spring water to the St. Johns impact mullet, shrimp, menhaden and bi-valve populations? And if so, what impact will that have on redfish, seatrout, flounder, tarpon, and near-shore species such as Spanish mackerel, kingfish, cobia, and others?

No one knows, and that’s precisely the point. Because none of this bodes well for the St. Johns, its aquatic plants, and fish. Nor does it set a good precedent for river conservation for anywhere in America.

Many people have believed for many years that the tragic flaw of Florida, and perhaps much of America, is the finite amount of pure, clean, freshwater available to its citizens. The problems of the St. Johns and Central Florida may well be the unfortunate bellwether of things to come for all people and all manner of fish.

Bottom line here is if Florida and its agencies error, they should error on the side of state natural resources, not on the side of unbridled development and human encroachment. Because, ultimately, we are the river.